This is one in a series of articles that provide detailed and updated information about Dentin.

In this specific article, which focuses on Dentin – Pathologies, you can read about:

For additional articles about Dentin, see the Topic Menu.

Should You Remove the Affected Dentin?

When treating dental caries, one of the primary considerations is whether or not to remove the affected dentin. The decision to remove affected dentin can be complex, particularly in cases of deep carious lesions. The two main factors to consider when excavating caries are preserving tooth structure and removing infected tissues without exposing the pulp. Caries excavation should be performed as thoroughly as possible, but in very deep lesions, some soft dentin may be left to avoid pulp exposure and conserve tooth structure. This approach can result in better bond strength and improved prognosis when restoring the tooth.

To make an informed decision about whether to remove affected dentin, dental professionals can employ the concept of the Peripheral Seal Zone (PSZ). This concept focuses on understanding the different layers of carious dentin and their respective characteristics:

- The outer infected layer: This layer is completely demineralized, contains denatured collagen fibrils, and cannot be re-mineralized. It should be removed during cavity preparation.

- The inner affected layer: This layer is partially demineralized and infected, but the collagen fibrils remain intact. This layer is sensitive and can be re-mineralized, so it should be preserved whenever possible.

Caries-detecting dye can differentiate between these layers by staining the outer layer dark red and the inner layer light pink. Caries-detecting dye can be used to confirm a caries-free margin, ensuring that 1-2 mm of superficial dentin is free of caries. Ideally, caries excavation should be limited to a depth of 5 mm from the peripheral surface of a tooth when measured from the proximal tooth, with an optimal depth of 3 mm.

In addition to caries detection dye, DIAGOdent technology, which is based on laser fluorescence, can also be used. This device provides a numeric value corresponding to the approximate number of bacteria present. For superficial dentin, the endpoint reading is approximately 12 or less, while for intermediate deep dentin, it is 36 or less.

Adopting the PSZ concept in treating deep caries lesions can help achieve bond strengths of approximately 45-55 MPa. By combining caries-detecting dye and DIAGOdent, clinicians can be guided on the proper way to excavate infected dentin while preserving the affected dentin within the peripheral seal zone.

How Long Can a Cavity Stay on Dentin?

The progression of a cavity on dentin can vary depending on factors such as the individual’s oral hygiene habits, diet, and the size and location of the cavity. In general, if a cavity is left untreated, it will continue to grow and eventually reach the inner layer of the tooth known as the pulp, which contains nerves and blood vessels.

It is difficult to determine a specific timeline for how long a cavity can stay on dentin, as the rate of decay can be influenced by a number of factors. However, it is important to address any signs of decay as soon as possible to prevent further damage to the tooth and potential infection. Regular dental check-ups and cleanings can also help catch cavities early on and prevent them from progressing.

Can Dentin Heal Itself?

Dentin, calcified tissue beneath the tooth’s enamel, that forms the bulk of the tooth, can be damaged when a tooth suffers trauma or decay. The tooth’s innate repair mechanism has its limits and can only produce small amounts of tissue under specific circumstances. Therefore, under normal conditions, teeth cannot heal themselves. However, studies have shown that stimulating tooth stem cells can aid in the natural repair of teeth when supported by Tideglusib, a drug commonly used to treat Alzheimer’s disease. By activating these stem cells, new dentin can be produced in an attempt to repair the damage.

Another area of research is the use of biomaterials, such as bioactive glass or hydrogels, which can mimic the tooth’s natural environment and stimulate the regrowth of dentin. These materials can be incorporated into dental fillings or used as scaffolds to promote the regeneration of dentin, improving the long-term prognosis of the tooth.

Dentin Staining and Discoloration

Dentin discoloration occurs when the color of the teeth changes, causing them to lose their bright or white appearance. Teeth may darken, shift from white to various shades, or develop white or dark spots in certain areas. Some common colors associated with dentin discoloration are:

- Yellow: As you age, the white enamel surface of your teeth may wear down, making the yellow dentin core of your teeth more visible

- Brown: Tobacco use, dark beverages like tea or coffee, and poor brushing habits leading to tooth decay can cause teeth to turn brown

- White: In young teeth, excessive fluoride exposure can cause white spots. This condition, known as fluorosis, occurs when teeth come into contact with excessive fluoride from drinking water or overuse of fluoride rinses or toothpaste

- Black: Tooth decay or tooth pulp necrosis can turn teeth grayish or black. Chewing betel nuts may also cause black teeth. Exposure to minerals like iron, manganese, or silver in industrial settings or supplements can create a black line on your teeth.

The causes of tooth discoloration can generally be classified into the following categories:

- Extrinsic, meaning it is caused by external factors that come in contact with your teeth

- Intrinsic, meaning it is caused by internal factors within your teeth or body

- Age-related, occurring later in life

Why is Dentin Yellow?

Dentin is the second layer of the tooth, typically covered by enamel and surrounding the pulp. It makes up the majority of the tooth’s structure and contains tiny tubules. Dentin has a natural yellow hue, which can be seen through the tooth’s enamel, and especially when the enamel layer is eliminated (due to pathologies or during dental treatment) and the dentin is exposed.

Can Dentin Be Whitened?

Dentin is the hard, calcified tissue that forms the bulk of a tooth, situated beneath the outer enamel layer. Unlike enamel, which is naturally white, dentin has a yellowish or brownish color.

During the whitening process, the target is the enamel, the outer layer of the teeth. Only stains on the enamel can undergo whitening. When a bleaching or whitening agent is applied, it breaks down into small particles on the enamel, removing stains by forming small molecules. However, dentin is not the area where whitening is typically performed.

There are some treatments that claim to whiten dentin, such as micro-abrasion, where a dentist removes a small amount of the tooth’s surface layer to reduce stains, and internal bleaching, where a bleaching agent is placed inside the tooth to lighten its color, such as in the case of endodontically treated teeth. However, the effectiveness of these treatments cannot be guaranteed.

It is also worth noting that excessive or aggressive attempts to whiten dentin can lead to tooth sensitivity or damage. Therefore, it is important to consult a dentist before attempting any whitening treatments.

Yellow Dentin Treatment

While there may be no sure way to whiten or bleach dentin, other methods can be used to address the yellow color of dentin. Before attempting correction, it is important to identify the cause of discoloration, which can include aging, genetics, trauma, or certain medications.

Some methods that can help improve the appearance of yellowed teeth include:

- Internal Bleaching: In cases of pulp necrosis, teeth may appear yellow or brown. In such instances, a dentist may recommend internal bleaching, which involves placing a bleaching agent inside the tooth to lighten its color.

- Microabrasion: This technique may be effective in treating yellow dentin that is close to the tooth’s surface. During this procedure, a dentist removes a small amount of the tooth’s surface layer to reduce stains and improve appearance.

- Veneers: These thin, custom-made shells are placed over the front surface of teeth to enhance their appearance. Veneers can be made of porcelain or composite resin and can effectively cover yellowed teeth. This option can be used for more extensive areas as well, where multiple teeth require aesthetic correction.

Dentin Dysplasia

Dentin dysplasia is a rare genetic dental disorder that affects dentin formation. It is characterized by defective dentin formation, severe tooth hypermobility, and spontaneous dental abscesses or cysts occurring in clinically normal-appearing crowns. Radiographic findings may reveal obliteration of all pulp chambers, short, blunted, malformed or absent roots, and periapical radiolucencies of non-carious teeth. Dentin dysplasia is estimated to affect approximately 1 in 100,000 people.

Dentin dysplasia can be classified into two types:

- Type I: Radicular Dentin Dysplasia

This type primarily affects the roots of the teeth and is further classified into four subtypes (1a to 1d) as described below. The common feature in all subtypes is the presence of abnormal root development, which can lead to tooth mobility and other dental issues.- Type 1a: Characterized by the absence of pulp chamber and root formation, with frequent periradicular radiolucencies.

- Type 1b: Displays a single small horizontally oriented crescent-shaped pulp, with roots only a few millimeters in length, and frequent periapical radiolucencies.

- Type 1c: Features two horizontal or vertical crescent-shaped pulpal remnants surrounding a central island of dentin, significant but shortened root length, and variable periapical radiolucencies.

- Type 1d: Exhibits a visible pulp chamber and canal with near-normal root length, large pulp stones located in the coronal portion of the canal that create localized bulging in the canal, root constriction of the pulp canal apical to the stone, and few periapical radiolucencies.

- Type II: Coronal Dentin Dysplasia

Also known as coronal cemental dysplasia, this type is characterized by abnormal dentin formation in the crown of the tooth. Teeth affected by this type of dentin dysplasia have a normal appearance but may exhibit abnormal pulp chambers and pulp stones. Radiographically, the teeth may show a “thistle tube” appearance of the pulp chamber, which appears wider at the top and tapers towards the bottom.

Dentin Sclerosis

Dentin sclerosis is a condition in which the dentin within a tooth becomes hardened and less permeable. Also known as sclerotic dentin, it typically occurs in response to chronic, low-grade irritation or trauma to the tooth. Dentin sclerosis is commonly seen in older teeth and can be associated with caries (tooth decay caused by bacterial activity), attrition (gradual tooth wear from chewing), or abrasion (Tooth wear from external mechanical forces). It may also be part of the natural aging process, as dentin becomes more mineralized over time.

When noxious stimuli are present, odontoblasts generate a protective response that results in the deposition of peritubular dentin in the dentinal tubules. This process obliterates the tubules, causing the dentin to appear more homogeneous and opaque. In a ground section (under microscopic examination), such dentin appears as a “white” zone with a homogeneous appearance.

While dentin sclerosis does not typically require treatment, it can make the tooth more brittle and prone to fracture. In some cases, a dentist may recommend placing a dental restoration, such as a crown or filling, to provide additional support and protection to the tooth.

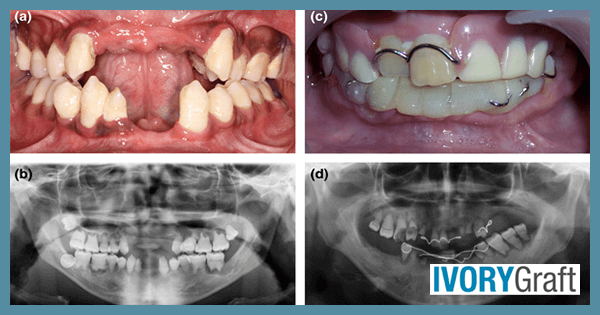

Dentinogenesis Imperfecta: Causes, Symptoms, and Treatment

Dentinogenesis imperfecta is a genetic condition characterized by defective dentin. It results in teeth that are translucent and discolored, typically blue-grey or yellow-brown. Due to the defective dentin, teeth are weaker than normal, and they may exhibit small surface pits or fracture easily. Dentinogenesis imperfecta is caused by genetic changes in the DSPP gene and is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. The condition can affect both primary and permanent teeth.

There are three types of dentinogenesis imperfecta:

- Type I: Occurs in individuals with osteogenesis imperfecta, a genetic condition in which bones are brittle and break easily.

- Type II: The most common type of dentinogenesis imperfecta, it usually occurs in people without another inherited disorder. Some patients with type II may also experience progressive hearing loss as they age.

- Type III: Typically occurs in people without another inherited disorder. First identified in a group of families in southern Maryland, type III has also been observed in individuals of Ashkenazi Jewish descent.

In each case, treatment depends on the specific dental issues experienced by the individual, and may include dental restorations, crowns, or other interventions to protect and support the affected teeth.

Dentinogenesis imperfecta can present various symptoms, which may include:

- Discolored teeth: Affected teeth may be gray, brown, or blue-gray, with translucent edges.

- Weak or brittle teeth: Teeth might be weaker than normal, making them prone to fractures or damage.

- Abnormal tooth shape: Teeth can be small or misshapen, with crowns appearing bulbous.

- Sensitivity: Teeth may be sensitive to hot or cold temperatures and pressure from biting or chewing.

- Delayed tooth eruption: Affected teeth might take longer to erupt or not erupt at all.

- Increased risk of dental decay: Weakened dentin structure can make teeth more susceptible to decay.

Addressing dentinogenesis imperfecta may require a multidisciplinary approach involving restorative, prosthodontic, and orthodontic treatments. For pediatric dental treatment, options include crowns, simple removable space maintainers, and adhesive restorations. The treatment can vary depending on the stage at which it is done.

Early treatment objectives include:

- Maintaining dental health and preserving the vitality, form, and size of the dentition

- Providing an esthetic appearance to prevent psychological issues

- Ensuring a functional dentition.

- Preventing loss of vertical dimension

- Maintaining arch length

- Avoiding interference with the eruption of remaining permanent teeth

- Allowing normal growth of facial bones and the temporomandibular joint (TMJ)

Treating mixed and permanent dentition is challenging and often demands a multidisciplinary approach. Collaboration between pediatric dentists, prosthodontists, and orthodontists is crucial. Although caries may not be a significant concern, strict oral hygiene instructions and preventive treatment are essential to prevent additional complications. It may be necessary to reestablish the vertical dimension of occlusion to restore mixed and permanent dentition. Prosthetic restoration combined with orthodontic treatment can be advantageous, and evaluating occlusion prior to initiating treatment is advised.

Dentin Caries: Causes, Progression, and Prevention

Dental caries, also known as tooth decay, is a multifactorial microbial infection that results in the demineralization of the tooth’s inorganic part and the destruction of the organic part, leading to cavity formation. This common oral health issue is caused by bacteria, such as Streptococcus mutans, that produce acid which erodes tooth enamel. The acid is produced when bacteria in the mouth break down carbohydrates from the food and drinks we consume.

Caries can be classified according to the site of occurrence (“G.V. Black classification”), as follows:

- Class I: Cavities in pits or fissures on occlusal surfaces of molars and premolars; facial and lingual surfaces of molars; lingual surfaces of maxillary incisors.

- Class II: Cavities on proximal surfaces of premolars and molars.

- Class III: Cavities on proximal surfaces of incisors and canines, not involving the incisal angle.

- Class IV: Cavities on proximal surfaces of incisors or canines, involving the incisal angle.

- Class V: Cavities on the cervical third of facial or lingual surfaces of any tooth.

- Class VI: Cavities on incisal edges of anterior teeth and cusp tips of posterior teeth.

Caries can also be classified according to severity, as follows:

- Incipient: Lesions extending less than halfway through the enamel.

- Moderate: Lesions extending more than halfway through enamel but not involving the dentin-enamel junction (DEJ).

- Advanced: Lesions extending to or through the DEJ but not more than half the distance to the pulp.

- Severe: Lesions extending through the enamel, through the dentin, and more than half the distance to the pulp

Risk factors for cavity and tooth decay include:

- Inadequate Oral Hygiene Habits: If brushing is not done regularly, plaque accumulates, harboring bacteria that produce acid, which directly attacks enamel until cavities form.

- Acids from Bacteria: Excessive consumption of sugary food and drinks leads to the production of acids in the oral cavity, which can result in the demineralization of enamel and cavity formation.

- Dry Mouth: Saliva production helps flush harmful bacteria, plaque, and food particles from your mouth. Reduced salivation, which can occur in certain medical conditions, makes teeth more susceptible to caries formation.

- Medical Problems: Some medical issues, such as bulimia, increase the risk of tooth cavities by exposing teeth to stomach acid each time the individual purges.

Prevention methods for caries

Caries risk assessment is based on factors such as past caries experience, current caries index, oral hygiene measures (e.g., using fluoride toothpaste and mouth rinse), calculus deposits, deep pits and fissures, and salivary flow. These factors can help assess individual caries risk and predict dental caries progression.

Preventive measures for dental caries, based on risk type, include:

- Daily Plaque Removal: Brushing, flossing, and rinsing are among the best ways to prevent dental caries and periodontal disease. Proper techniques should be followed for both brushing and flossing.

- Fluoride Application: Methods include water fluoridation, fluoride toothpaste, fluoride mouth rinse, dietary fluoride supplements, and professionally applied fluoride compounds such as gels and varnishes. Fluoride prevents dental caries by inhibiting demineralization and enhancing remineralization, resulting in a more acid-resistant surface.

- Pit and Fissure Sealants: The majority of dental caries in young children occur in pits and fissures, which are more susceptible due to their anatomy. By filling these irregularities with flowable restorative material, the area becomes sealed to bacteria and therefore less susceptible to caries. This is especially recommended for young patients with erupting teeth and adults with a high caries index.

- Sugar Substitutes: As sucrose is a well-known cause of dental caries, sugar substitutes like xylitol have been developed to reduce caries risks. Xylitol not only has a sweet flavor comparable to sugar, but it is also non-cariogenic and anti-cariogenic, blocking sucrose metabolism.

- Caries Vaccines: Since dental caries is an infectious microbiologic disease, there have been attempts to develop vaccines. Some experimental vaccines against Streptococcus mutans have shown success, and immune interventions can be undertaken by blocking receptors necessary for colonization or by inactivating glucosyl transferases (enzymes involved in glucose metabolism).

- Reducing Transmission: Primary caregivers can transmit caries-causing microorganisms to infants, resulting in the colonization of Streptococcus mutans in the child’s oral cavity. Efforts to reduce Streptococcus mutans levels in the parent, including maintaining oral hygiene and undergoing dental treatment when necessary, are crucial for preventing dental caries in young children.

Dentin and Dental Caries Risk Assessment

Risk assessment is a valuable tool for the prevention and management of dental caries. Various risk tools and models can be used for risk assessment, including:

- The International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS)

- The International Caries Classification and Management System (ICCMS)

- Association Caries Classification System (ADACCS)

Following are descriptions of each of these systems:

- The International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS)

Based on this method, the visual appearance of a lesion classifies the lesion (i.e., detection, whether or not the disease is present), helps in monitoring the lesion once detected (i.e., assessment), and diagnosis.

The system scores clean, dry teeth and estimates caries activity based on the histological extension of lesions spreading into tooth tissue. The scores use a 7-point rating scale:

| Score | Decay Level | Visual Appearance |

| 0 | None | No decay |

| 1, 2 | Initial | “Intact” enamel lesions |

| 3, 4 | Moderate | Early, shallow, or micro-cavitations |

| 5, 6 | Extensive | Late or deep cavitations |

- The International Caries Classification and Management System (ICCMS)

This system takes the results of the ICDAS classification and translates them into a risk-assessed caries management system individualized for the patient.

The key elements of ICCMS are:

-

- Initial patient assessments

Collecting personal and risk-based information through histories and systematic data collection

- Lesion detection, activity, and appropriate risk assessment

Detection and staging of lesions, assessment of caries activity, and caries risk assessment

- Synthesis and decision-making

integrating patient-level and lesion-level information

- Clinical treatments

Surgical and nonsurgical, including preventive treatment, thus ensuring that the treatment planning options available are prevention-oriented and include nonsurgical options whenever appropriate

- Initial patient assessments

- Association Caries Classification System (ADA CCS)

The ADA CCS incorporates the ICDAS and other classification systems into a broader classification system that also includes radiographic presentation of the approximal surface and clinical presentations.

The ADA CCS is conducted on clean teeth, using compressed air, adequate lighting, and a rounded explorer or ball-end probe. Radiographs should also be available. This system is designed to include both non-cavitated and cavitated lesions and to “describe them by clinical presentation without reference to a specific treatment approach.”

ADA Caries Risk Assessment forms categorize a patient’s overall risk of developing caries based on history and clinical examination. The forms are designated for patients ages 0 to 6 years and older than 6 years.

Characteristics that place a patient at high caries risk include:

-

- Sugary Foods or Drinks: Bottle or sippy cup with anything other than water at bedtime (ages 0 to 6 years) or frequent or prolonged between-meal exposures/day (ages >6 years)

- Eligible for Government Programs: WIC, Head Start, Medicaid, or SCHIP (ages 0 to 6)

- Caries Experience of Mother, Caregiver, and/or other Siblings: Carious lesions in the last 6 months (ages 0 to 14 years)

- Special Health Care Needs: developmental, physical, medical, or mental disabilities that prevent or limit the performance of adequate oral health care by themselves or caregivers (ages 0 to 14 years)

- Chemo/Radiation Therapy (ages >6 years)

- Visual or Radiographically Evident Restorations/Cavitated Carious Lesions: Carious lesions or restorations in the last 24 months (ages 0 to 6 years)

- Non-cavitated (incipient) Carious Lesions: New lesions in the last 24 months (ages 0 to 6 years)

- Cavitated or Non-cavitated (incipient) Carious Lesions or Restorations (visually or radiographically evident): 3 or more carious lesions or restorations in the last 36 months (ages >6 years)

- Teeth Missing Due to Caries: Any (ages 0 to 6 years) or in the past 36 months (ages >6 years)

- Severe Dry Mouth (Xerostomia; ages >6 years) or Visually Inadequate Salivary Flow (ages 0 to 6 years)

In summary, comprehensive dentin and dental caries risk assessment plays a crucial role in modern dentistry. It allows dental professionals to identify high-risk patients, provide personalized care, and implement preventive measures that contribute to better oral health outcomes for individuals and the community as a whole.